Cash-value life insurance could prove to be a valuable asset for clients looking to couple an insurance need with tax and portfolio diversification in retirement. But there are some major caveats involved. Product considerations are complex and numerous, and using this strategy inappropriately in a retirement income plan can trigger major pitfalls for clients.

Cash-value life insurance, the most common form of permanent insurance, comes in a few flavors: whole life and categories of universal life, such as variable, indexed and current-assumption. Each has an insurance component providing a death benefit, as well as a separate, tax-advantaged cash-accumulation component earning investment interest that can be tapped during one’s life.

The tax treatment is a big selling point. Investors fund the policies with premium payments, which grow tax-deferred; investors can access the principal and accumulation tax-free, if they adhere to specific guidelines, via withdrawals and policy loans. Heirs ultimately receive a tax-free death benefit.

As such, advisers say the policies can serve as a retirement-income supplement if clients (typically the very affluent) have maxed out their contributions to vehicles such as 401(k)s and individual retirement accounts and want another to park tax-advantaged money.

If advisers consider the cash value of a low-cost, long-term whole life policy as a part of a fixed-income portfolio, the policy generally will provide more income per dollar than bonds held in taxable or tax-sheltered accounts, said Michael Finke, professor of personal financial planning at Taxa Tech University.

Tax-bracket management and reduction of sequence-of-return risk are the best two ways to use cash-value polices in retirement, according to Jamie Hopkins, the Larry R. Pike chair in insurance and investments at the American College.

For example, if a client needed an additional $10,000 in a given year but would bump into a higher income-tax bracket by taking that distribution from a traditional IRA, a withdrawal from a life insurance policy could be beneficial because it wouldn’t increase the client’s taxable income. (Withdrawals reduce a policy’s death benefit, however, some advisers would have to weigh whether pulling from a Roth account would be more advantageous.)

Similarly, advisers can use the same principle to help manage client’s monthly Medicare premiums, which rise according to specific income thresholds. Withdrawing from a policy could also help a client defer Social Security claiming as long as possible, to age 70, to maximize benefits. Further, if the stock market falls during the early years of their retirement, investors can withdraw from a life insurance policy rather than lock in losses by selling riskier assets in other areas of a portfolio. “That can really help over the long run,” Mr. Hopkins said.

There are limits to the tax-advantaged contributions investors can make to the policies, which are set in relationship to the initial death benefit purchased and can be much higher than those of 401(k)s and IRAs.

Thomas Archer, CEO and founder of The Archer Financial Group, who specializes in writing whole life policies for ultra-high-net-worth individuals, has clients who fund policies with tens of thousands of dollars in annual premiums and others who fund in the millions.

Life insurance policies are similar to Roth accounts. They aren’t subject to required minimum distribution rules. Nor are there penalties for tapping money prior to 591/2, unlike traditional 401(k)s and IRAs.

All of the above benefits, though, become moot in the event of a misstep. Investors must withdraw their basis, the aggregate premium payments first, and any investment appreciation second. Gain can only be received tax-free in the form of a policy loan from the insurer, which can be paid back (with interest) while the policy is in force or subtracted from the death benefit at the policyholder’s death.

The danger of withdrawals and policy loans is what Scott Witt, a fee-only insurance adviser and owner of Witt Actuarial Services, refers to as the “surrender squeeze,” when withdrawals and loan interest build up to such a level that the investors must make more premium payments or lapse the policy. In that case, not only would the client lose death protection, but a tax bill would be due on any investment gains in the policy at ordinary income tax rates rather than the more favorable capital gains rates.

“I think it can be oversold, and some people are purchasing it who shouldn’t.” says Scott Witt, a fee-only insurance adviser and owner of Witt Actuarial Services.

Basically, if policyholders can’t sustain a policy until their death, it can be “particularly devastating” because they’re left with a huge tax bill and nothing left to pay it, according to Witt. “If you can get a well-designed product in situations where it makes sense, I think it can be very appealing,” he said. “But like a lot of things, people who it makes sense for [are buying it] but aren’t purchasing optimal policies.”

It’s not only withdrawals that can cause these lapses, either. Life insurers such as Voya Financial, Transamerica Life Insurance Co. and AXA Equitable Life Co. have been in the spotlight recently because they raised the cost of some in-force universal life insurance policies.

Absent regular monitoring and an increase in the underlying cost of insurance could lead policies to lapse more quickly than expected, especially if policies are structured for flexible premium payments rather than recurring level premiums. If an investor doesn’t make a premium payment in a given period, the cash value can over insurance costs, and higher costs could deplete that cash value if the investment interest were lower than anticipated. (Note that using the cash value to pay premiums reduces the death benefit.) What could compound the lapse problem is an overreliance on life insurance illustrations, the primary life insurance sale tool. Illustrations, which show hypothetical valuations for policy performance over time, can be overly rosy and therefore misleading for advisers.

Last year, The National Association of Insurance Commissioners adopted new rules, called Actuarial Guideline 49, for indexed-universal-life illustrations to tamp down on some insurers’ unrealistic policy projections. What this all boils down to is the need for stead-fast due diligence from advisers. “Using life insurance for retirement income is something that is growing in popularity, at least among the advisers to the rising affluent and high-net worth individual,” Barry Flagg, president and founder of Veralytic Inc., a life insurance research and rating provider. “But it must be treated like any other retirement vehicle”, according to Mr. Flagg. That means comparing policies not by using illustrations, but by looking at the cost of insurance and expenses as well as what the historical performance has been on the invested asset underlying cash values.

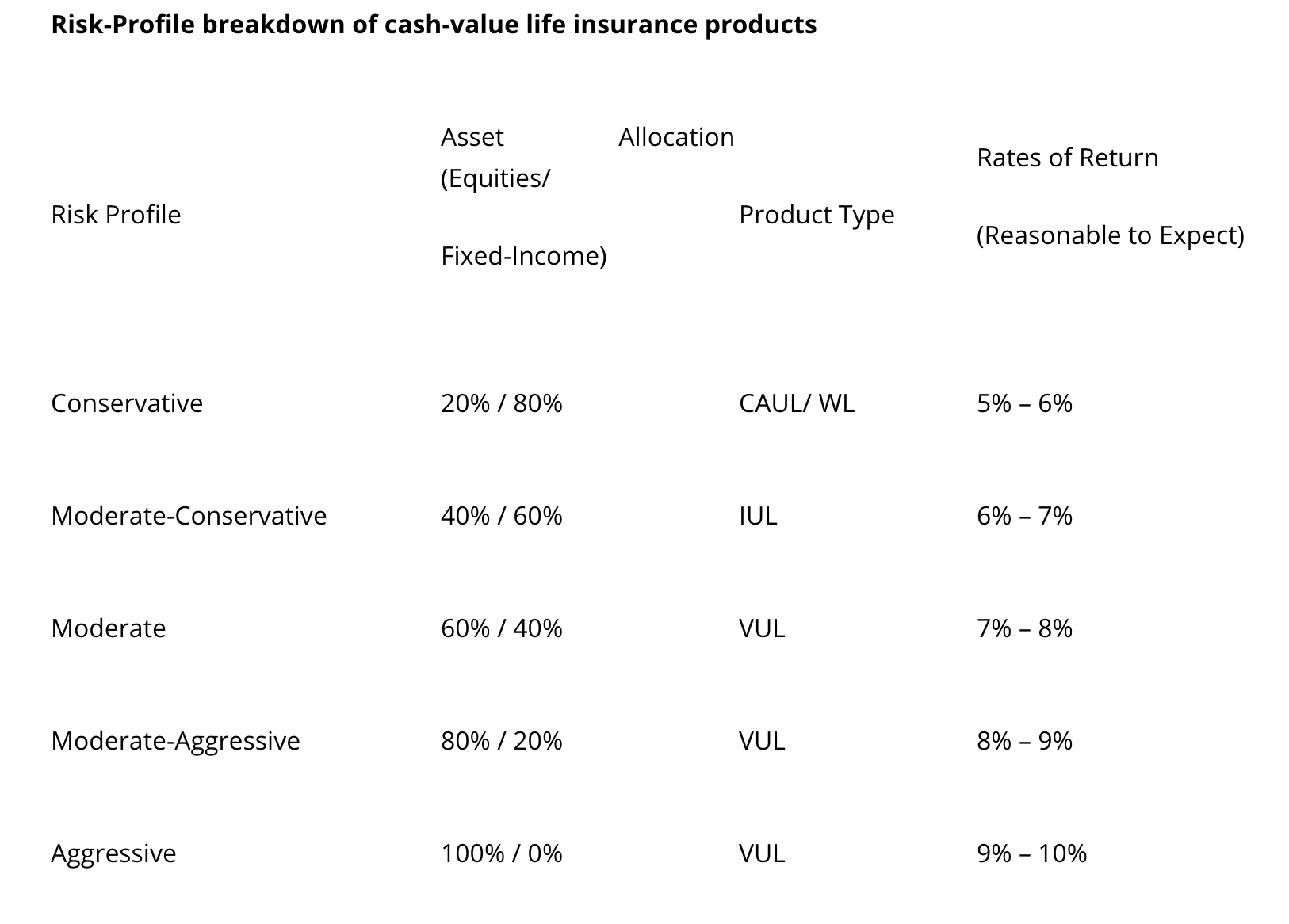

A good policy would be one with low internal expenses, a track record for delivering expected return and investment options consistent with investor’s risk profile, he said.

Whole life, current-assumption universal life and indexed UL would typically be considered the more conservative products of the group, with variable universal life being the most aggressive.

Whole life, which tends to be offered by mutual insurance companies, and universal life, typically offered by stock companies, credit interest based on the performance of insurers’ general accounts. IUL is also a general-account product but credits interest based on the performance of a market index like the S&P 500 and typically offers a 0% crediting floor in the event of down markets. VUL invests premiums in mutual-fund-like separate accounts, at the policyholder’s discretion.

From a pure investment standpoint, most whole life policies have an advantage over UL policies because they’re more often funded through regular, rather than flexible, premium payments, which allows the investments supporting whole life policies to be more aggressive, longer term and less liquid, according to Mr. Witt, a life insurance actuary who formerly worked at Northwestern Mutual. Long term, those characteristics should enhance the yield of whole life investment portfolios, he said. However, UL becomes relatively more appealing in a heavy-distribution scenario because it’s generally able to withstand much heavier borrowing and remain in force longer than whole life, Mr. Witt said. It’s not necessarily that overall value (distributed income plus death benefit) is higher with UL, but it can sometimes provide more income for clients, he added.

That said, many believe those buying cash-value life insurance should see value in a death benefit to justify the insurance costs. “If you don’t need the insurance, it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense,” said Neal Kerins, vice president of product development at John Hancock Insurance, a universal life insurance provider. “Investors must also be fully committed to holding the policies long term, until death, because they don’t pay off otherwise.”

“It’s extremely inflexible in the early years,” said Gary Olsen, a partner at Lenox Advisor Inc. “It’s a terrible short-term investment.” That said, he is an advocate of whole life insurance, especially in low-interest-rate environment like the current one, in which policies are likely to earn more than fixed-income instruments.

“In practical application, people do buy term insurance but don’t invest the difference.” – Jayne Alford, managing director of the insurance group at the Independent Financial Partners. Policy costs are higher than tax savings over the short term, said Mr. Flagg of Veralytic; conversely, taxes due on taxable investments are higher than policy costs over the long term. Therefore, it makes the most sense to buy life insurance by age 50 when planning to use it as a retirement vehicle, he said.

According to a joint study on individual life insurance from the Society of Actuaries and LIMRA, an industry group, whole life policies sold between 1994 and 2009 had first-year lapse rates ranging from around 9% to 14%, gradually decreasing to around 2% to 3% for policies held more than 21 years.

To prevent involuntary lapses, some insurers offers a feature called an “over loan protection rider,” mainly on UL policies, that aims to prevents a policy from lapsing and triggering a taxable event. Some carriers also have a premium deposit account, similar to a savings account, out of which the insurer can cover policy expenses so the cash value in the policy isn’t depleted, according to Channing Schmidt, senior advanced marketing counsel at Securian Financial Group, who works with advisers on life insurance case design.

Ultimately, investors with permanent insurance end up with more money over the long haul than those who buy term insurance policies and invest the remaining assets in outside accounts, due in part to behavioral finance. “In practical application, people do buy term insurance but don’t invest the difference, said Jayne Alford, managing director of the insurance group at Independent Financial Partners, a hybrid registered investment advisor.

Automating savings, or structuring consistent, level premium payments, makes it much easier to project future cash accumulation, Mr. Hopkins said.

May 29th, 2016